Election flyers time! Go here for part 1, the Communist Party flyer.

This week, the French are voting for the first round of the presidential elections. It’s coming at a moment no one could have predicted as this tense, with Europe trying to wean off of its energy dependency as Russia is invading Ukraine. This has been one of the foremost issue in the recent weeks, all but eclipsing the rest of the election topics, and the corollary of gas prices has been at the forefront of the campaign (which is, in all honesty, a refreshing change from the usual fare of immigration and public safety).

Here is my readout of the the posters of the election.

This next poster could not be further from my personal political beliefs, but it’s also one that has things to say, if only as a cautionary tale. Let’s see if you can guess the party’s leanings:

So, I should say that this was kind of a trick question: in France the blue is for conservative parties, and the red is for left-wing parties. This color-coding is very old, and dates back to the post-World War I era, when the elected chamber was heavily peppered with veterans. French soldiers wore blue pants and jackets in the trenches, and a deep blue coat for ceremonies (with very visible red pants), so the elected chamber was nicknamed “blue horizon”. The government subsequently nominated (France had at the time a similar constitution to Italy now, so the Chamber’s dominant party or alliance of parties determined who was to be Prime Minister, while the President held a largely representative function and was not elected by direct universal suffrage) was led by Clémenceau, a war hero, and was an assemblage of right-wing party later known as the Nationalist Bloc. Thus blue came to be associated to the French equivalent of the US Republicans today, and the red, for the socialist and communist conferences, were used as left wing colors. In 1920, at the Tours Congress, the French SFIO, which until then had been a single party, split into the Democratic Socialist Party, and the Communist Party, and they adopted respectively pink and red as colors in the later part of the century.

So, considering blue as a conservative color, deep blue is the color of very conservative parties in France, and in this case a nationalist party, the Rassemblement National (formerly the Front National). A brief history (okay not so brief) of the FN:

It’s almost 8pm when the Citroën DS of President Charles de Gaulle leaves the Elysées Palace on a warm and dry summer–in fact France is undergoing a major drought, following an exceptionally cold Spring. At 8:10pm, on a roundabout of Le Petit Clamart, a town Southwest of Paris (near Versailles), a man standing near his SIMCA car waves a newspaper. Unbeknownst to the General, his wife Yvonne, their son-in-law Alain (who is also the General’s aide de camp), the chauffeur, and the secret services agents following in the next car, this is the signal a band of terrorists from the OAS was expecting. The Secret Army Organization, a terrorist organization essentially formed by a coalition of organized crime bosses, and army officers, was dead-set against Algerian independence. Despite their work to undermine it, bombing and attacking indiscriminately Algerian groups and French government positions and officials, independence had happened earlier that summer, in 1962. The year before, they’d frustratedly watched the Algiers putsch attempt fail when the military commanders of Oran and Constantinople had stayed loyal to De Gaulle (a French resistance hero, and a revered war commander of the French Free Army during WWII).

As my father tells the story of the putsch, De Gaulle placidly told the anti-independence “I understood you,” and then threw everyone in jail. It’s a tad bit more complicated than this (sorry Dad!): De Gaulle’s government had heard about the putsch through the secret services. The day of the putsch, after a message announcing the military had seized control of Algiers awoke the city at 7am, De Gaulle had a general and several other officers and civilians compromised in the Coup arrested. The next day, in a foreboding move that Juan Carlos will steal in 1981 in Spain, De Gaulle appeared on television at 8pm, in full 1940 uniform and regalia (including his multiple medals he’d already earned before and during the war, as De Gaulle was a very good military strategist). He called onto soldiers and civilians to stop the Coup, stating that the quartet of generals and their officers who had seized power were only the face of a secret army of fanatics who saw the “Nation and the world [only through] their distorted delirium.” He concluded his call with the outcry: “Frenchmen, Frenchwomen! Help me!”

Thanks to transistor radio, his call was heard all over Algeria, and conscripted soldiers, the real unsung heroes of the failed Coup, rose up against their commanding officers. Just like in Vietnam, many already questioned the legality of what France called “a special police operation,” especially in the face of increasingly hostile world coverage. So when their C-I-C asked them to stand down and prevent the fall of the Republic, conscripts heard him live. And answered in kind.

This was the De Gaulle that the OAS was attacking–not the one who would be revealed later to have facilitated the rise of his own private militia, the SAC (Service d’Action Civique-Civic Action Service) through his secret services’ careful management of organized crime in Algeria. De Gaulle had a mythical status, which only grew after the attempt on his life.

The OAS shot over 150 bullets that day, but fortunately for De Gaulle and his entourage, the shooters were either poorly trained or the drivers were very good, and none of the De Gaulle family members died. The front tires of De Gaulle’s DS were blown, but thanks to the world-famous hydraulic suspension Citroën is known for, the car stayed on the road and was able to drive away to the Villacoublay airport, its original destination. De Gaulle and his wife were saved by the quick eye of their son-in-law, an army colonel, who reportedly shouted to his father-in-law “To the ground, Father!”. As a side note–it’s not the first time De Gaulle was under fire: he famously stayed upright and calm as snipers were raining bullets on the Te Deum mass he’d called for in Notre-Dame, at the end of WWII, so his reputation as being fireproof was nothing new, but stories were immediately born about him staying upright in the car, which isn’t true. If he’d stayed upright, he would have been killed–but thanks to the quick-thinking of his son-in-law, he dodged to the ground and was saved. Another legend/potentially true but really impossible to verify was born that day around Yvonne, De Gaulle’s widely invisible wife, normally, (who was way more discreet than Mamie Einseinhower, so this story is quite out of character for her). Reportedly, as they arrived at the airport, Yvonne was only worried about one thing, the chicken. Chicken is the English equivalent of “pig”: it doesn’t just mean the animal, it’s also a slang for cops. “Did they shoot the chicken?”, bellowed Yvonne. No, answered the secret services, we are all well and good–but she was actually speaking about real chicken, the one they’d had delivered frozen from Fouchon, sitting in the trunk of the presidential car. The OAS operation was dubbed “Charlotte Corday,” by the way, from the anti-French Revolution activist who murdered Revolutionary and French Republic Founding Father Marat in his bath (“They couldn’t corrupt me, so they murdered me,” he supposedly wrote/said as he died), so you can probably gather where the democratic system was going after De Gaulle’s assassination, in the OAS’ wildest dreams.

Those officers got caught, but the grumbling opposition, built on former paratroopers (most of whom were guilty of torture and genocide in Algeria, but never saw the front of a La Hague tribunal, because France), continued through political groups like the GUD (Group Union Defense) or the ON (Organisation Nationale/National Organization).

In the late 70s, these people saw with increasing alarm the rise of François Mitterrand and his socialist party (ah, the good old red scare that justifies every fascist attempted coup, including the possible support of the CIA to the Algiers Coup in 1961!). Before the 1973 legislative elections, they started to organized more formally, but it was after Valérie Giscard D’Estaing’s failed reelection that they started on the national scene for good. Not that they were very happy with VGE to start with–but his loss came with the rise of Mitterrand, and that was the scarier part.

Le Pen was a former paratrooper, who was never tried for torture–but there is circumstantial evidence he participated in special operations with the goal of kidnapping Algerian civilians. Over the years, he has widely denied these allegations, benefitting from anecdotical stories such as the fact that he was one of the few officers who, in Algeria, had Muslim enemy fighters buried with Muslim rites (allegedly, Krim Belkacem, one of the leading figures of the FLN, the Algerian freedom fighters group, told him in 1970 that he escaped assassination attempts only thanks to his attention).

What’s certain: JMLP was born into a blue-collar family, and had always had a reputation for trouble. In high-school, he got expelled for fighting and reputedly lost his right eye in a fight. During his years studying for his law JD, he reportedly was so flamboyant and combative that he was asked to step down from his VP position in the Student Council.

The independence of Algeria primed him for the waiting arms of the extreme-right organizations of France, and he became increasingly close, before and after it, to OAS members.

JMLP is obsessed by French history, and he doesn’t like the path the Republic is on, especially the rise of postcolonial immigration. A few examples: in 1963, with a former French volunteer of the Waffen-SS, Léon Gaultier, he opened a music business specialized in editing military music and historical speeches (you can guess which type of speeches he published). In 1972, some members of the Order Nouveau (New Order, a sinister nationalist and antisemite organization close to former pro-Vichy and Waffen-SS veterans), impressed by his publishing work, asks him to become a candidate for the legislative elections in a newly founded party the National Front. Shortly thereafter, JMLP seized control of the group.

Le Pen is a talented public speaker, but the specter of the Vichy Regime is too close still, and his party stagnates below the 5% scores. On November 2nd, 1976, a bomb destroys part of his Parisian apartment. Marine, his youngest daughter from his first marriage, is 8, and she is traumatized.

This is relevant because it’s always been my theory: JMLP doesn’t believe half of the outrageous stuff he spouts. He is a troll. He relishes the attention, and, like Trump, he has very little core political convictions–his political sense is mainly built on several core beliefs: no one says no to JMLP, he is a born-brawler (think Ray Kelly, former commissioner of NYC and former Marine and boxer), JMLP is unpredictable, there is an international conspiracy against the sovereignty of nations, and democracy is bad because it is not willing to get its hands dirty to help him rise and protect everyone, Everyone Is Out To Get Him, Authoritarian Regimes Are Good, Weak People Should Die. The rest is just a natural deduction of this. He is basically a fervent follower of the idea that the strong should govern and the weak should die, but he will also sell mother and father to get to the spotlight. That makes him a great demagogue, but not really a man of convictions.

I also don’t think JMLP ever expected to become president–like Trump he just enjoys the personality cult, and the ability to say uncensored bad crap. Don’t be mistaken–he is a Bad Dude (TM), but his over-the-top personality long stopped being directed at taking power. He just likes to troll.

His daughter, on the other hand, that’s another issue altogether–first-of-all, her world is very different from her dad’s: he lived through the 1976 bombing as an adult, and took it as a badge of honor, as a former veteran who had willingly conscripted to fight decolonization three times would.

She lived this as a helpless child, and Marine Le Pen does not do well with helplessness. (None of the Le Pen do). Her niece Marion Maréchal (her older sister Yann’s daughter) is even worse–she grew up in a widely reviled family, a wealthy one (Le Pen started paying the high fortune tax in France in 1982). She is basically third generation frustration, hatred, and nationalism, and that is never a great combination.

Back to Marine LP. When her dad stepped down (under pressure) from the party, it was mainly because the party was now steadily making scores over 10-15%, and stagnating. Some leaders in the party saw the Le Pen patriarch’s association with former organized crime bosses, and generally neofascist rabble, as disquieting and an obstacle in the rise to power of the party, especially in the context of both a reckoning with Vichy and the reality of the French resistance, which starting in the 1980s was finally depicted as it always should have been–a minority movement–, and the work to unearth Algerian archives the newspaper Le Monde started doing in the early 2000s.

Le Pen Sr had led the party to an unexpected second round in 2002, though unintentional (the left-wing candidate, Lionel Jospin, was uninspiring, fairly socially conservative, and bad at campaigning), but his trolling now kept the Front from power, because the party kept hitting the Republican wall, named not for the US or French conservative parties, but for the general, unspoken consensus that no Le Pen was ever to hold the top power position: any candidate who ended running up against the FN in the second round of whatever elections from top to bottom was the candidate *everyone* should endorse, even if that meant voting against your own conviction.

The widely unspoken agreement was: No Pasaràn. They Won’t Pass–the anti-fascist outcry of the Spanish Civil War in the 1940s.

More prosaically, opposition to the FN also led the French government to switch back to a majority vote (winner-takes-all) after a brief proportional election (each party gets MPs proportionally to its scores) in the early 1980s. Interestingly, Mitterrand is the one who made that change, ahead of what looked like a hot mess of an end-of-term legislative election. He walked it back immediately after it resulted in the election of 35 FN MPs.

This “bold” personality that had led Le Pen to power now was a hindrance, and combined with outrageously bad management in the few towns the FN could win in the 1990s, led the party to oust him, first from power, then to force him into retirement and out of the party in 2015.

His daughter was named as his successor. Marine, also a lawyer, has almost always held a job in politics, with one single-minded focus starting in the early 2000s: clean up the party, sever the ties with organized crime and former OAS officers, kick out antisemites, skinheads…Generally clean house and throw out the guys who screamed FASCISM. The FN was now a respectable party, much like the pretense of the alt-right white supremacist Richard Spencer.

This strategy led the FN to a number of town administrations in the 2000s, which they still hold for the most. It also brought Marine to a third place at the presidential election of 2012, behind Hollande (Socialist Party) and Sarkozy (the right wing incumbent)–but it should be underlined that she only placed third (with the highest historical score for the FN) through a combination of the Republican Wall, and the fact that Sarkozy campaigned so far to his right that he seemed somewhat virtually indistinguishable. Sarkozy had overstayed his moment, shocking the wider voting public with harsh anti-immigration declaration, and leading even my moderately conservative (center-right) dad to vote for the Socialist candidate, Hollande.

In 2017, Le Pen Jr rose to the second round, and that’s when things started to be more complicated: under the weight of the 2008 financial crisis (which Europe was still not recovered from, to some extent, in 2015-2016), and the combined new respectability and general apathy of left-wing voters, Le Pen passed the mythical 15% bar no one in her party had ever passed at a national election.

But then, she fumbled her answer in the televised debate, much like Nixon made a piss-poor performance against JFK, and got confused between two issues. It’s not so much that people voted for Macron, it’s just that her performance was so dramatically bad that the Republican Wall survived one more election, and she lost. There was also a strategic change in the way the Powers That Be dealt with her party: up until her, the conventional wisdom had been that any attempt at judiciarizing the known links of the family with more or less unsavory elements, or any attempts to look into the party finances, or possible organized crimes links, would result into the triumph of JMLP who would emerge as a martyr.

This strategy having shown its limitations, the omerta was lifted in the early 2000s. It led to JMLP being declared ineligible, and 6 judicial affairs emerging during the 2016 campaign. This, combined to her bad public performance, led to MLP losing. Unfortunately, almost despite herself, she also emerged with a 30% score at the second round, which was historically unprecedented and showed the erosion of the Republican Wall–well and also the fact that no one was really that hot for Macron, whatever he thinks. Macron is a technocrat–someone who’d never held an elected public office position before he ran for president, and that’s a species that’s increasingly hated in Europe.

Objectively, newspapers were right to be worried that MLP would be elected on the first round (something that’s never happened in French history but is technically possible if a candidate has more than 50% of the vote). Unfortunately for her, high abstention rates worked against her. I know, it’s not intuitive, but in France the alt-right has a solid youth and blue-collar base. Trump was elected mostly by suburban white people. Until late in the 2010s, these people in France did not traditionally vote for Le Pen if they were salaried employees. Only independent contractors voters voted for her. But now, Le Pen had managed to present the image of a modern woman, taking a leaf from Meg Thatcher’s book, and that strategy worked with the youth in France, combined with an increasing structural unemployment of youth (France has one of the highest youth unemployment rate in the EU).

Unfortunately for her, a campaign that was about as interesting as a dead fish, combined with the warning shot that Trump’s election was, combined to make her score lower than it should have been, and Macron got elected.

For the 2017 campaign, MLP is running into a bunch of unforeseen issues: the Ukraine war has transformed Macron into a war leader–and most Western democracies LOVE their war leaders, especially if it’s for a cause as popular as Ukrainian democracy, and against Russia. Another issue is the possible Russian financing of her 2012 campaign, and her relationship with Putin, which is now a poisoned gift.

And finally, a public figure has emerged at her right–it’s no secret that a bunch of former leaders of the FN (now RN) have been disenchanted with Marine’s “polished image” strategy, and see her moderation as a hindrance to their road to power. Amongst them is her own niece, who has risen to power meteorically, becoming the youngest member of parliament ever when she was elected at 22 in the lower chamber, back in 2012. Thus enters Eric Zemmour, the devil-she-must-deal-with, and who is making her look like an angel by comparison. He polled way ahead of her at first, but he seems to lose steam as the campaign is progressing, and now the second round seems to predictably be slated to be her vs Macron.

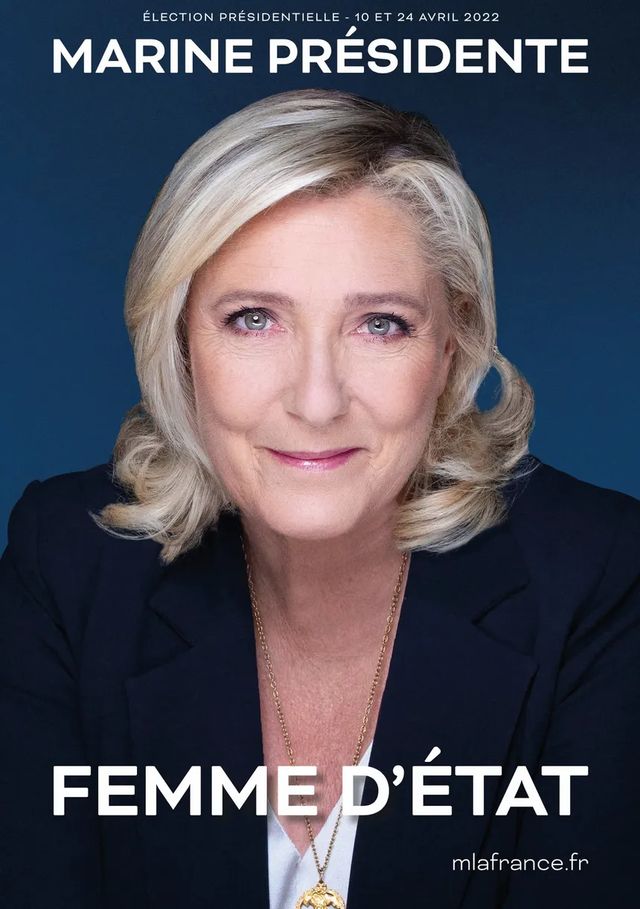

In terms of poster: she is doing a hard Thatcher sell here. Macron has been criticized for his relative youth and incompetence–she is showing an opposite side. It’s a sober poster, with a unified dark blue background, by contrast to the dark blue, much more informal poster of the first round in 2012 (which was strangely similar to a Sarkozy one, btw), or, God forbid, the campaign aberration of 2017, which showed her sitting on her desk with a short skirt. I have no idea who thought it was a good idea to choose a second round poster like this, but she quickly discovered what showing a “more vulnerable” or “sexy” side implies for women in politics: this poster, against Macron’s poster of the time, made her out to be too young, strangely younger than, and more incompetent than the guy who was running against her, potentially the youngest president ever, and also someone whose only background was holding a ministry and studying public affairs. This second round should have been much harder for Macron, but this communication mistake combined with her debate fumble made it a slam dunk even for someone as unappealing as Macron.

She’s learned from her mistakes, and she has thatcherized her image considerably here, which is smart (hey, I don’t make the codes, blame my patriarchal home country for it). Even the choice of a discreet gold pendant and a straight face contrasts with the disaster that was her weird tilt on the 2017 second round poster. The white shirt below her dark blue tailor helps bring in a nice contrast, but it also veers attention away from her chest, when her 2017 poster over-sexualized her. It’s a boring poster, and she is selling the respectable female politician hard, and playing the “responsible woman” card super hard, but contrasted to the disaster that is Macron’s poster this year, it finally makes her look like the experienced politician she didn’t look like in 2017.

Never underestimate Marine Le Pen. Many have made this mistake before, even finding her nice in contrast to her dad.

But when fascism knocks again, it’s not going to be wearing Stormtrooper uniforms, as goes the popular meme.

It’ll wear the suit of a formerly-chain-smoking-survivor-female-politician, who’s likely going to survive Eric Zemmour against all odds.

Again, Le Pen is not the imbecile her niece makes her out to be. She might have mastered the art of saying nothing and vacuous political speech, but she is not dumb.

Let’s see if her strategy of respectability bears its fruit–she is also playing her skin here, as her niece’s desertion to Zemmour shows.

Leave a comment