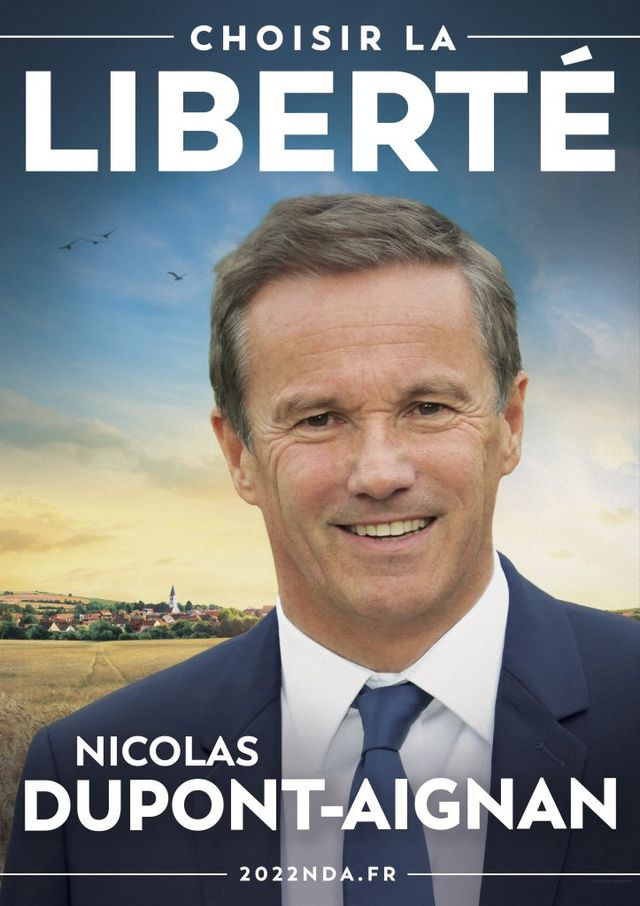

I am not, believe it or not, in these posts about the first round of the election, not trying to alternate between left and right wing candidates, it just so happens that this one caught my eye almost at the same time as the previous one I posted about (Nathalie Arthaud and the Workers Party). I’ll let you guess the political spectrum of this guy, but then we are going to have to talk about him in greater depth.

Nicolas Dupont-Aignant is not per say a right wing candidate, but he is somewhat of an UFO in French politics: a nationalist, sovereignist, anti-EU, anti-NATO candidate who also happens to not be (in appearance at least) a totally horrible human being, and also happens not to be mentioning the word immigration over and over and over again in his program (twice inside the leaflet if I’ve counted correctly, and on his website none of the major proposals deals with immigration per say, outside of a vague “let’s close the Schengen space). We will see in a minute that he’s not without problems, but NDA attempts to navigate the line between left and right with proposals that he draws from both, and he’s so far been very successful at sounding actually like he is a nice guy (he’s…problematic to say the least, but he is not Marine Le Pen, although that is a low bar).

First, let’s get something out of the way: NDA is one of the oldest running candidates in this election. By this I mean that he’s one of only 3 candidates who’s been running in every presidential election since 2012 (this is his third–the other two are Marine Le Pen, and the far-left candidate I’ll talk about next, Jean-Luc Mélenchon).

NDA has cultivated, since the start, two things: one is his positioning as the only true heir to De Gaulle’s legacy. This is a recurring theme in the right, of course: De Gaulle founded the postwar right wing in France, and had to walk the line of getting away from the conservatives who’d been installed in Vichy, while not outright condemning Pétain, whom he respected as a WWI hero. He legitimized his party as a republican right through his own figure, and it got increasingly hard for the right to detach itself from him. Interestingly, while De Gaulle cultivated this image of debonair, fair, honest and strong leader, he knew perfectly well how to maneuver the political scene, and there is more than one murky thing happening under his leadership, behind the scenes–he found his own party in 1947, the Rally of the French People. The RFP was founded in Strasbourg, my hometown, which is a very interesting proposition, because many decades later, in 1971, the Postal Bank of Strasbourg, Avenue de La Marseillaise, will be the stage of a massive bank robbery–some call it the heist of the century–in which a billion Francs (about the same in today’s euros) were whisked away in 5 minutes from the hallways of the Central Postal Bank in Strasbourg. This money was stolen by the so-called Lyonnais Gang, formed around ex-SAC officers. The SAC (Service d’Action Civique) was a militia formed by De Gaulle to protect the interests of his party and his policies.

The Strasbourg billion, it’s now more or less an open state secret at this point, was used as a war chest by the successor to De Gaulle’s UDR (itself the successor of the RPF), the RPR, founded in 1976. At this point, the people who claimed De Gaulle’s heritage were well-known figures of the French conservative parties of the 1990s: Jacques Chirac and Charles Pasqua–Pasqua was, in short, the Don Corleone of French politics. He had his hands in illegal casinos, oil trading, armament, illegal cigarette trading, and according to Newsweek was friends with most of the preeminent mafia figures of Corsica, the South of France, and Lyon. He was perhaps the single-most corrupt politician on the 1970s-1990s, although not the only one, but you’ll find more than one French person who remembers him fondly, despite the Pasqua laws that deprived children of foreign parents born on French soil of the jus solis citizenship rights. A lot of this fondness has to do with his record on security during his stints as Minister of the Interior–he is most remembered for being the guy who ordered the French assault police to nail the terrorists who’d taken a plane hostage in Marseille to the door, likely preventing a 9/11 style kamikaze operation.

This is the party that NDA loved, and while De Gaulle promoted the reconciliation between France and Germany, and the construction of Europe to put an end to the slaughter of young Europeans, the RPR of the 1980s and 1990s wasn’t exactly pro-EU. Under the impulsion of Pasqua, the RPR is best remembered as the party that introduced the campaigning style that prevails today, and which is centered around a TV debate during the 8pm news between the first and second round, between the two top candidates (a format they stole to Kennedy, btw, and which turned against Chirac in 1988, when he famously asked Mitterrand to stop treating him as his Prime Minister, and instead consider the two of them as two candidates on equal standing–to which Mitterrand answered with a pithy: “Yes, Mister Prime Minister.”). Pasqua was vehemently anti-Europe, but as his grasp on the RPR slipped (he was radioactive to Chirac, who’d successfully taken control of the party, risen to president after Mitterrand stepped down, and managed to bury his less than savory past under a giant rug), so did his anti-European proclivities. Chirac then transformed the party into the UMP, to support his late 1990s political ambitions, and Pasqua’s loss of influence became felt in the (apparent) support Chirac gave to the European constitutional treaty (I say apparent because he jettisoned that very nicely by putting it up to a popular referendum and used it as a way to sow discord in the Socialist Party).

The RPR, as I showed above, and then its successor the UMP, was also a party of “financial affairs” that only Mitterrand was able to equal on the left. Very few leaders of the party, including NDA who ran against Alain Juppé to become head of the party before leaving it, would have ignored some of the most unsavory aspects of the above, although it’s probably only Pasqua and Chirac were privy to the links between the SAC, the Strasbourg bank robbery and their party. But NDA did not leave it because of his integrity, no, he left it when it became clear that the right was becoming more neoliberal and pro-globalization.

His second stick is very Pete Buttigieg–he was for a while the mayor of a Paris region town, who has very high electoral approval rates, and is selling himself on the national stage because, you know, he was a good mayor to a town of less than 30, 000 people.

Interestingly, the town he was the mayor of is a very very not at all rural town. Here is the satellite picture of Yerres:

Yerres is part of a string of towns that surround Paris. It’s a fairly indebted town, and while you might say it has some green spaces (with a forest in the South and a hill on the North), it would be a stretch to say it’s the countryside. As the mayor of Yerres, NDA conducted a center right policy: fiscally conservative (debt renegotiation, cancelling of infrastructure updates), somewhat centered on public safety (creation of a forest police unit to prevent drug selling in the forest south of the town, CCTV cameras everywhere), but somewhat socially and environmentally friendly (creation of municipal, rent-controlled housing, use of recycled pool water to clean the streets, use of low-voltage lightbulbs in the streets, special housing for abused women, publicly stocked open pantry for low-income families). Yerres has, and would be defined, as a suburb, clearly not a rural town.

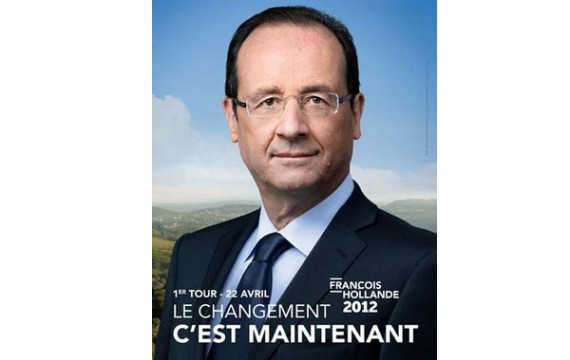

Still, that’s the background NDA chose–and to be fair, while he is the only one who has done it this year, historically, having a rural village behind you is a fairly common place thing. Look, for example, at this poster, which is Hollande’s 2012 presidential campaign effort.

So, granted, France stayed a massively rural country much much much later than most Western European countries, in part thanks to an infrastructure that was designed to service and feed Paris, and nothing else much. But France, like most Western countries today is defiantly not a rural country. 80% of the French live in what’s considered a city, and more than one French out of two lives in a city bigger than 100, 000 people (which is, like, a lot for a country of about 67 millions people). There are rural spaces left, but generally, much like in the US, it’s not what I’d call the dominant feature of French demography. Yet, in almost every single election since 2002, candidates have either had a village, or a cow (or a baby cow) in the back. In a country where the Agricultural Fair in Paris every year is a hit show, that’s somewhat understandable–but it’s also disquieting because it is geared towards an anti-modernity outlook. The France of the villages, the one the two children protagonists visit in the book “Le Tour de France par deux enfants” (Two children’s tour of France, a nationalist book made to teach children how beautiful their country was after the traumatizing defeat of 1870 against Prussia, which features a chapter on the Lost Provinces of Alsace and Lorraine), is a vestige of the nationalist past of France. Ironically, historically, that is the France that Parisian politics of the Republic have tried to harmonize, homogenize, and generally culturally destroy (see the bloody columns of Vendée), so it’s funny to see it as a model of true France.

It’s a similar movement as the one when Sarah Palin talks about “true America”, a trope that’s existed since Mark Twain and the pastoral novel, which took root against the urban novel, except it does not have the Frontier connotation in France. In fact, I don’t think Palin would like this rurality very much, because it calls back to a pre-capitalistic, pre 19th century France, a rurality where mutual assistance was a dominant force, perhaps as much as it calls back to a more homogenous, religiously and racially speaking, France.

That’s what both Hollande and NDA are going for, ironically from opposed standpoints.

Rural France is too often treated with contempt by Parisians, and its inhabitants thought of as second-rate citizens by internet and infrastructure providers. In my mother-in-law’s village the top internet speed is about twice as slow as my hotspot in my rural village of 6,000 people in the US.

There is a layer in this village background of this: the callback to a country where solidarity and your neighbor were the prime concern of local governments–it’s not necessarily a strong callback to pre-capitalism times, as Hollande’s choice probably indicated, but it’s a callback to simpler times with no right or left wing. NDA’s program is a good illustration of this: it calls for a greater popular power, the end of social inequality, and less contempt for the France that’s not Paris.

The additional layer with NDA’s poster, which does not exist in Hollande’s 2012 campaign poster is the very preeminent church in the background. NDA is a Christian conservative, and one of those people who opposes secularism where Christianity is concerned, but loves to tout it when Islam makes an appearance.

And that is the fascinating part of this particular campaign–while NDA is known for saying things like “there is so much anti-white racism in France,” “we should stop the immigration flow,” and very clearly has very variable beliefs in term of secularism, he manages to not be dubbed as a racist. He’s got a reputation for being on the left of MLP, in all likelihood because he is fond of the popular referendum (think White House petition), and because he is very vocal about social inequality.

It’s logical in his case–he dislikes neoliberalism on the principle that it gives an unfair advantage to global International corporations, so the rural village is also a way to be somewhat anti-capitalist, without having a demonstration in the back (he comes from the party of Law and Order after all). But make no mistakes: the France that NDA harks back to is one of cultural homogeneity and whiteness. NDA is anti-immigration, even if the word immigration only appears twice in his 16 proposals for France on the website highlighted above. He’s also a very fervent partisan of the “racism against white people theory”. And, interestingly, he poses here as a defender of provincial France–that should make him logically opposed to the left’s Jacobin and centralist political model, but no. NDA is vehemently against the European Charter to Protect Minority Languages (if you read French, this is what he writes about it). Publicly, he even decried the victim syndrome of pro-regional language groups that, according to him, presented regional languages as an endangered species when they were now taught in public schools.

FYI: that is a gross misunderstanding of what the Jospin 1999 reform of education is about. It introduced the possibility of taking an optional “regional language and culture” exam at the end of high school degree, the baccalaureate, but I have never met anyone who did not have any prior local language education, got to high school, and got taught enough regional language to be fluent while in public school. . And re: the regional languages no longer being threatened–Alsace would like a word with NDA on the subject. In 1997, there were 80% of Alsatians who were speakers of the local dialects in one way or another. It’s now down to 50%, and only about 25% of Alsatians can pass it to their children (about 10% only use it predominantly at home, against close to 30% in 1997). If that is not disappearing, I don’t know what it is.

Finally, the “Choose freedom” slogan: NDA is a huge opponent to public health measure taken during the pandemic. For him, and a number of former Marine Le Pen entourage members, the health measures taken by the French government are a dictatorship that’s fascism (totally the same as concentration camps, obviously). To choose him is not only to choose integrity (ha. As if he never knew what was happening in the RPR in the 1990s!), but also to choose a France that’s not lost its social net of yesteryear–that part where, before communists tried to take over France–society was family, faith, culture, and solidarity-based.

It’s odd to think of NDA as a good guy, but this is what the poster screams.

But it also screams of a very white, very male, very traditional values France, which sure is pre-colonization and fairer, but is also a France that a) does not exist anymore, b) is a disquietingly homogenous society with very little place for difference, including regional difference. NDA is happy to celebrate “local cultures”, but one wonders what these are without languages. This is also one of the reasons the extreme-right wing has done better locally than many conservative parties, big or small like NDA’s: in the 1990s, Jean-Marie Le Pen’s national front was the only one which sent programs translated in local languages for local and national elections. It was also one of the few, if not the only party at the time, to have a cohesive French Caribbean and French oversea territories strategy, which explains the strong foothold it had in predominantly black territories: if you want to get to people like this, it’s not by evoking the spirit of 1789 and a Jacobin understanding of languages not at as a strength but as a destructive force off the Republic, which is the reading mainstream parties have done in France since about 1875 of regional identity (they are old, archaic, dangerous). People at the fringes of the Republic, who’ve been treated by it as something to civilize and put in line, don’t take well to being dictated policies by people who’ve never stepped foot in their territories, in the name of an abstract egalitarian Republic that awfully looks like cultural annihilation to them (see the recent riots in Corsica).

Freedom yes, but for whom, and from what?

Leave a comment