Next! I’m going to run fast through the next few, as they are now small scorers, and I also did not manage to finish this before the first round ended.

The next party is a refoundation of an old staple of politics:

Jadot is running for the left-wing party EELV (Europe Ecologie les Verts). EELV was born of the coalition of several small parties or altermondialistes (alternatives to globalization) personalities going together first in the 2009 European elections. The Europe Ecologie part is an amalgamation of several environmental and social justice figures, such as José Bové (an activist fighting against GMOs, corporations, and globalization with unrestricted trade). It wasn’t meant to be a professional party, but rather a coalition of individuals with a same concern for the environment and a social platform of justice and fairness. The Green Party, on the other hand, has a long history on the French political scene, if not one that’s fairly confidential. It’s existed mostly through the coalition that it has forged, and the environmental parties in France have had a complicated history. There are or were, officially, about four green parties or clubs in French politics. The best known is EELV, the fusion of Europe Ecology and the Green Party. The Green Party itself has existed more or less since the 1970s, although it was apolitical in a way at its foundation, choosing a non-aligned position (neither left nor right wing) in the 1980s. This position became untenable in the 1990s, when it became clear that the conservative parties of France were not going to join the environmental effort (partially because in the 1990s, hunters and fishermen were still a political force). The best-known representative of the Green Party in France, and the person who perhaps can be considered its Founding Father and spiritual Father, is Antoine Waechter. Born in Mulhouse, Alsace, Waechter was the main figure behind the “neither right nor left” effort, perhaps as a concession to his pragmatic Alsatian education: common sense has no political party. In Alsace, he is most known for his efforts to reintroduce, with great success, the beaver, which had been hunted into extension, and then had to fight for resources and territory with the nutria, an invasive species from South America particularly easy to recognize from its orange front teeth. The nutria, as a side note, is a good illustration of climate change: until the 1980s, it was relatively rare in Alsace, because it cannot survive long winters and harsh climates. In the 1990s, the effect of climate change being felt increasingly, the continental summers of Alsace (hot and humid a good portion of the summer) and now warmer winters made it a perfect home for the nutria, and its population exploded. The nutria is particularly happy to consume corn, which has become somewhat of a monoculture in some parts of Alsace, and it enjoys the stem of the invasive algae that is now a common sight in the many urban canals of the region (these plants are themselves a good hint of global warming: they thrive in warmer waters and suffocate all the other vegetation around them). They’ll occasionally feast on American crawfish that’s also an invasive species (but no one is unhappy with that), and snails. Go walk in Strasbourg, and you’ll see many of these guys–it’s ubiquitous, perhaps more than in other big cities in France because Strasbourg is surrounded by water and marshes where they thrive.

Anyways. The Green Party left its neither nor position in the 1990s, to somewhat great success, and in the late 1990s, it ran with the Socialist and Communist parties in an alliance called the Pluralist Left (la gauche plurielle). It’s on the strength of that alliance that Lionel Jospin became Prime Minister after the disastrous lower chamber dissolution Chirac made in 1997 (he dissolved the Assemblée National because he couldn’t get what he wanted from its majority, in the hopes of getting a stronger majority, and to his surprise, he ended up with a left-wing PM because the alliance got the majority of the vote. Talk about miscalculation).

Generally though, the Green Party had been relatively modest until its alliance with the Europe Ecology movement, after the 2009 European elections. In the last European election, its strong position made EELV, effectively, one of the biggest parties in France, and translated in their win in several big cities in France (Bordeaux, Lyon, and Strasbourg, for example), but those elections don’t necessarily translate the national presidential one for several factors: one is that the European elections, for example, are largely ignored by voters and have very high abstention rates. But they also are easier for the EELV coalition to some extent because young pro-Europe people are more likely to find their programs relevant and interesting in the European parliamentary elections, as EELV is one of the most pro-European parties running. European regulations have frequently run ahead of French ones, so it’s easy to see Europe as an ally in the fight against environmental destruction, especially when the Green Party veterans can point to several transnational successes of the past: the reintroduction of the salmon in the Rhine River, for example, is largely an example of transnational European cooperation between Germany, France, Switzerland, Lichtenstein, Austria and the Netherlands. In the 1960s-1970s, the Rhine was a toxic dump wasteland, but thanks to coordinated efforts and millions of euros, there are now salmons reproducing naturally in the Rhine, although 8 French dams continue to block its travel in some parts of the Rhine, as well as port activity in the Netherlands. The goal is that within the next five years, salmon can run back from the estuary to the city of Basel unimpeded.

EELV is also surfing on a new phenomenon: the loss of interest of young French voters for traditional methods of civic expression like the vote, in favor of direct action and non profits. This has benefitted EELV because many of the most media-figures of the party are longterm activists (like José Bové, or even Jadot himself) who have ground experience in building momentum.

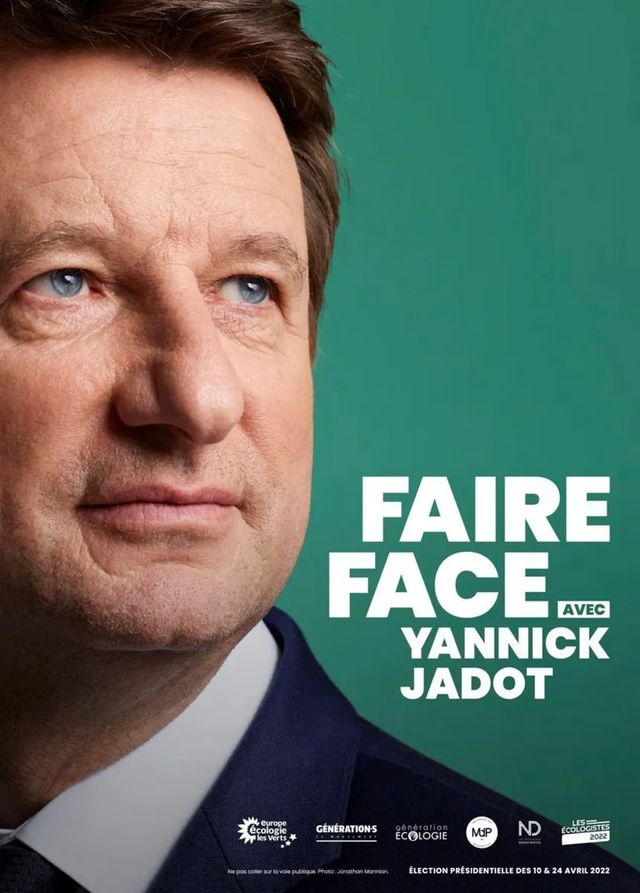

The poster above isn’t particularly bad, but it’s also not particularly imaginative: a green background seems almost like the obvious choice. The picture is interesting in that it gives a complete different story than the slogan here: to faire face is to confront reality, to measure up to what we have to fight for and against, but Jadot isn’t facing, he’s looking off to the right, above the shoulder of the audience. This discrepancy makes the poster less efficient, and more vague. The abundance of close ups in suits also doesn’t help this poster: it’s hard to distinguish it from the many other close ups.

All in all, it’s a forgettable poster, which is never a great thing in politics.

Leave a comment