My dissertation centers around four figures, four female travelers.

When I started working on travel research some years ago, what first struck me was the virtual absence of contextualized, wide-breadth work on female travelers in French Studies. Almost all work done on travelers tended–and still tends–to concentrate on extraordinary figures and very few works were interested in how publishing markets and gender constrained female travelers and how they negotiated it; as well as how the female body was at the center of politics of identity and race in the framework of a positivist and colonialist Third Republic.

Only three works were touching upon some of these issues in survey studies. Sara Mills, Dunlaith Bird and Bénédicte Monicat’s works were seminal in finding scholarship for me, especially Monicat’s Itinéraires de l’écriture au féminin.

For the purpose of my dissertation, I chose to work on four female travelers, covering the 1850s to the 1910s, a transitional era for female travelers who benefited from the explosion of tourism. These travelers dealt with the rise of French bourgeoisie’s ideal of femininity, centered around the spheres theory. Women’s place was in the hearth, and as such, they were essentially represented as immobile entities with little participation in active endeavors such as politics or exploration. The women I have chosen are representing themselves in public and civic spaces ordinarily refused to them.

Echoing Mills, Bird and Monicat’s works, my research project therefore asked the central questions: how do women travel? How do they represent themselves? How do they see themselves? How does one manipulate femininity and changes it? What is the place of women in the early Third Republic?

In trying to answer these questions, I discuss issues of gender representations in Fin-de-siècle literature as well as early twentieth century France; travel writing and ethnography and how women saw their place in the world; as well as gender ambiguity and the publishing market of the travel literature genre. I also touch upon the importance of the feminine and the masculine in relation to citizenhood: these women, who did not know each other, participated in various ways to the same intellectual experiment that was inspired by the century’s pursuit of nationhood, the rise of nationalism, and the building of empires, in an attempt to rebuild and reframe what citizenship meant. Conservative or liberals, all four of these women touched upon notion of femininity in the framework of what it meant to be a French, what right was one granted by this attribute, and how one could work toward a voice in public spaces. All of them bucked against the constraints that gender and genre imposed on them to question the place of women in civic spaces. All of these women, in their attempts to insert themselves in this discourse of the polis, one strongly delineated by the interest in Orientalism the French have, created a category of racial exclusion: if they were women, then at the very least they were white women, and as such they had duties and rights, if not that to vote.

The endgame of my research is less to glorify the extraordinary in these women, although their personal stories merit attention, but rather to rewrite them in the history of a positivist Republic to highlight the questions of citizenhood that arose in their era, and still continue to plague France today.

The four figures I am working on are listed here, with short biographies. You will also find the structure of my dissertation and short synopsis of what each chapters contains.

Olympe-Félicité de Jouval (1832-1890)

Born in Marseille, France, Olympe-Félicité de Jouval was married to Henri-Alexis Audouard, with whom she had two children. After separation from her husband, Audouard eventually went to Paris, where her numerous feminists pamphlets put her on the imperial’s blacklist. In 1868, to avoid jail time, Audouard left for New York City, to weather the storm out. While there, she became the first French woman to cross the United States by railroad.

Marie-Thérèse de Solms-Blanc (1840-1907)

Born in Seine-Port, a quiet Parisian suburb, Solms-Blanc was married at age 16 to a man older than her, financier A. Blanc. Their short but tumultuous wedding ended three years later in a separation, and Blanc only saw her husband again thirty years later, at her son’s wedding. In the meantime, having no wealth left of her own, Blanc took the penname Th. Bentzon, and started writing for multiple papers and magazines, including the prestigious Revue des Deux Mondes.

Her travel journal, written after a trip of almost a year to the United States in 1893-1894, Les Américaines chez elles (The American Woman at Home, Harper and Sons), was an almost instant bestseller, and the most comprehensive work of the century on education in the United States.

Jeanne Henriette Magre (1851-1916)

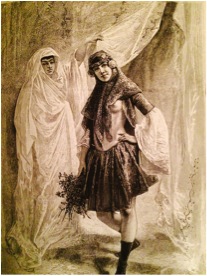

Magre, better known under the name Jane Dieulafoy, is widely considered the first female archeologist of France. Born in Toulouse, Magre married civil engineer Marcel Dieulafoy. In 1870, Marcel willingly signed for military service, and Jane followed him, dressing as a male aide de camp to Marcel. From then on, Jane traveled her entire life dressed as a young man, a privilege she was even granted on the continent by the French government.

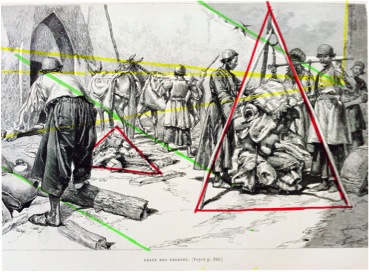

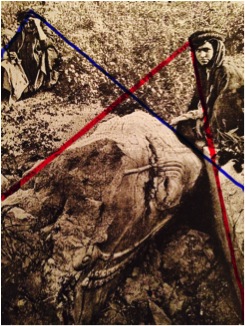

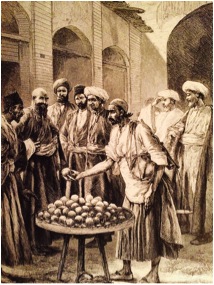

Dieulafoy’s luxurious journals were published by Hachette when the couple got back from their travels in Persia. Along with the literary recognition that came with the books, the opening of two rooms at the Louvre dedicated to the couple made them perfect instruments of propaganda for the colonial efforts of France.

Isabelle Eberhardt (1877-1904)

Amongst my four sources, Eberhardt is the only one who is not French. Swiss of Russian family, Eberhardt moved throughout her life, wandering around the Continent and the Maghreb with her mother. In the late 1880s, after her brother had joined the Légion, and was assigned in Algeria, Eberhardt took an interest in North Africa, where she moved with her mother. The two converted to Islam, and, after her mother’s death, Eberhardt joined the resistance against French occupation. Eberhardt’s alter ego, Si Mahmoud Essadi, traveled throughout North Africa, getting in contact with the Sufi resistance. In 1901, she was attacked in an apparent murder attempt fomented by the French government. In 1904, she died, after saving her husband, an Algerian soldier, in a flash flood in Algeria. Most of Eberhardt work was published after her death, mainly because of censorship from the government.

Chapter Division

My dissertation is divided in two parts:

- American Travels, with Audouard and Bentzon’s journals in the United States

- Northern African Travels, which includes Dieulafoy and Eberhardt’s works.

In Part One, I mainly discuss Audouard and Bentzon’s precarious condition as travelers and their attempts to minimize the readers of the time’s possible anxieties in regard to their condition as travelers, but also how their trip to the United States allowed them to discuss new types of femininity, and notably possible citizenship participation for French women in voting rights. I briefly look at their attempts at ethnography to identify the central focus of upper class femininity, motherhood and the family.

In Part Two, I discuss extensively the evolution of the female traveler’s position and self-image through the apparition of the gaze’s motif in Dieulafoy and Eberhardt’s texts, but also the continuous use of gender ambiguity as a way to overwrite Muslim presence. Additionally, I show in depth how nationalism and power functions in the context of the publishing world and the way Dieulafoy and Eberhardt are evaluated and published–and this of course includes talking about 20th and 21st century attempts to sanitize racism and nationalism in French re-editions of both authors. Part Two also considers the role of citizenship and gender in the construction of empires and memories, as well as the relationship between photography and the evolution of travel journals, from cosmographies to biographies.

I successfully defended my work on April 25, 2016.

Some examples of photographs by Dieulafoy that I analyze in Chapter 3.

Leave a comment