I’ve been going around in circles trying not to talk about this guy, for whom I have no personal affinity, but we are trying to talk about presentation, not my personal taste. I will let you guess what political color he is.

Yup, it’s hard.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Méluche as some of his base calls him, is a far-left politician. His ideas are not that far off of the Communists, with whom he presented a common platform and candidacy in 2012, but they are somewhat distant this year, for many reasons.

Okay, so now that I’ve talked about how thoroughly unsavory the French right is, and the far-right Le Pen family, I need to add the Socialist party to this, which is great because then I won’t have to repeat this later on for the actual Socialist Party candidate, Anne Hidalgo. To put Mélenchon on a US scale, first, I’ll say he’s probably around Bernie Sanders (complete with the race representation issue, btw). He’s probably a little to the right of the Squad. Like Bernie (although I don’t know if Bernie would define himself formally as such), he is a historical materialist–and that drives his vision of racism in France, which is really really color-blind (Bernie has somewhat the same issue in that he’ll answer “it’s the economy” to every questions on systemic racism, fortunately he’s got the Squad in his corner to rectify the progressive record on this). It also drives his vision of what constitutes capitalism, labor relations, the trajectory of history, and the idea of nationalism. On the latter, I have to underline that the predominant vision of history amongst the historian community in France espoused a form of historical materialism for a very substantial part of the 20th century, for example on the idea of what led to the birth of nationalism and the idea of nation-state, or the history of economic relations in France. It took the influence of the Annals school, and particularly of Fernand Braudel, for the discipline to escape from under the thumb of Marxist views of the world, particularly, to say broadly, the vision that economies and labor forces only drive history.

Unfortunately, a lot of politicians don’t seem to have made that switch, and that limits their ability to read the room, especially in terms of intersectionality. Méluche is one of those people, just to position him on a number of philosophical and historical issues.

To back up a little: Mélenchon started his political career in the Socialist Party. Under François Mitterrand, he became a prominent regional leader, and then was elected on the higher chamber, the Senate (the Senate is not elected by voters directly, but by indirect suffrage through elected officials, so it’s traditionally been more conservative, making his election quite outstanding). JLM grew up in Morocco, when it was still French, and was born there (he is what we call in French a “Pied-noir”, a Blackfoot). He’s got a very traditional left-wing background: one or two school teacher parents, went to college, and became a high school teacher before he rose up through the rank to senator and later undersecretary of education, under the Jospin government in the later part of the 1990s.

In the 1980s, when he rose to a more prominent place in the Socialist Party (PS in French), the party was dominated by larger-than-life leader François Mitterrand.

If Pasqua was the Don Corleone of politics, Mitterrand was the Lucky Luciano (minus getting caught): same flashy tastes and sense of staging. Mitterrand grew up in a catholic, conservative bourgeois family of Jarnac, a small town north of the Gironde Estuary and Bordeaux. Mitterrand grew up comfortably: their house had an electrical system already in 1922, which wasn’t rare in my home region of Alsace, thanks to German ingenuity during the German occupation of 1870-1918, but was exceedingly rare in the rest of France in the 1920s, minus Paris of course. Mitterrand was, and is still, exceedingly popular in some circles of the PS, although his legacy is now murkier.

In short, Mitterrand started off as a nationalist activist, and cozied up to a lot of unsavory criminals before he moved to the left. In the 1930s, young Mitterrand was close to militants of the far-right terrorist group La Cagoule. He regularly participated in xenophobic demonstrations after the 1929 financial crisis reached France in 1932, and wrote in the column of a newspaper he freelanced for how desolate he felt about the internationalization of the Quartier Latin in Paris (employing with great effect the trope of the Babel Tower, something the French revolutionaries of 1789 LOVED, see Abbé Grégoire’s Report on the situation of French in France in 1793).

During WWII, Mitterrand first served as a non-com officer in the Maginot Line, after which he was sent east as a POW. He escaped though, and started his own network of resistance, after first joining a Pétain group, which complicates his war legacy.

The French resistance was partially left-wing (essentially communist), and partially nationalist–although antisemite, xenophobic and rabidly anticommunist, the French nationalist movements could not condone the idea of Germany as a master, especially after WWI, which was still fresh in many memories. Mitterrand joined the fight and used his cover as a volunteer in Pétain’s French Legion of Volunteers (a vet group serving as moral caution to the Nazis and Vichy). During the way, he Mitterrand received a very prestigious award from Pétain’s hands for his service to Vichy. According to left-wing politicians, and resistants he served with, they all knew he was receiving it, and he essentially received it because they were using him as a mole and it was a perfect cover.

This is the murky part of his legacy there: Mitterrand is the guy who participated in the liberation of the Dachau and Kaufering camps, where he found his friend Robert Antelme and saved him from typhus–Antelme went on to write of the most important books of the war in French, L’espèce humane (The Human Species) where he describes his life in the camps. But Mitterrand also vouched for, along the founder of L’Oréal André Bettencourt, for Eugène Schueller, a sinister individual who was part of the leadership of La Cagoule. Mitterrand joined after the war the “Republican Left”, an assemblage of people who were left-wing but anticommunist.

This is where I should underline that in France, the JOC was a particularly active pre and postwar group. JOC is the acronym for Young Christian Workers (Jeunesses ouvrières chrétiennes), a similar movement to the YMCA, but more to the left of the YMCA. Founded in Belgium in 1925 by Fr. Joseph Cardjin, the movement was an assemblage of socialist and generally humanist left-wing activists, who sought to help workers movements across the globe, and who were deeply embedded in Christian communities. Even though in the 1960s the movement took a hard-left turn that increasingly distanced it from the Church and people like Mitterrand, the popularity of the movement explains why, in France, and Europe, part of a generation of children born on or after 1925 frequently joined the JOC and were deeply invested both in a Christian ideal as well as left-wing and humanist policies. The JOC was part of the resistance during WWII, and out of its three cofounders, only Fr. Cardjin survived the war.

Before he turned away from it, Mitterrand was part of numerous associations linked to the JOC and the JEC (Jeunesses Etudiantes Chrétiennes). It was very frequent and very common at the time–and the secularism of the socialist party was not anywhere as entrenched as it is now. The JOC stayed very popular until its hard left turn in the late 60s–my own mom was part of summer camps organized by the JOC, many Jesuist priests were part of the JOC, including the one who oversaw my dad when he was a summer camp counselor. What we see now as an incompatibility between religion and social progress in France was a given in the 1920-1960s period, and even beyond (many JOC leaders called their members to vote for Mitterrand in the 1980 presidential campaign). Mitterrand was not an UFO–his catholic roots and socialist allegiance were not out of the ordinary for the times. Mélenchon, our candidate above, started off in this tradition: he worked as a freelance cartoonist for a Christian newspaper, and he’s been known to give interviews to major Catholic newspapers like La Croix, which other left-wing candidates tend to avoid.

Mitterrand’s career is marked by absolute control over the PS starting in the late 1970s. It’s hard to say the extent to which his unsavory dealings with the Cagoule and his underground dealings helped him, but let’s say the Socialist Party of the 1970s-1990s was not unfamiliar with what we call in French “le bourrage d’urnes”, a term that speaks to the tradition of fake voters in primaries (this past year, a dog and a dead guy voted in the right-wing party’s primary, so that’s not a tradition of the past). The Socialist Party of the pre-war period was a Socialist party deeply steeped into the workers union movements, and it relied on a network of non-profits. There were big figureheads of the Left at the time, like Jean Jaurès or Léon Blum, but the 1936 social net wins were very much a collective, concerted effort. The postwar period, both in the Communist and Socialist Party is driven by men who’ve just spent four years fighting in the resistance, and welcome the type of cultist, strongman figures that Marx is so fond of. In the 1970s, the right and left start to crystallize around two big figureheads who will dominate the 1970s-1990s, Jacques Chirac and François Mitterrand. They have a lot in common, although on polar opposite sides of the spectrum: they are both deeply involved in financial dealings that would have them jailed (fictional jobs with paychecks given to friends, blackmarket type of dealings etc), they both have numerous affairs (Mitterrand had at least two illegitimate children and although Chirac does not have any official illegitimate child, there’re long were rumors of a son in Japan, a country whose culture he admired and loved. Also, full disclosure, my great-uncle, René Sieffert, received high awards from Church who admired his work on Japanese literature, but I have no hidden sympathy for Chirac because of this, rest assured).. They also both belonged to the free masons, came from somewhat opposite side of the spectrum and moved to the other side as adults: Chirac from a secular and republican (in the left wing sense of the early 20th century definition) of teachers, Mitterrand from a conservative Catholic family.

As long as Mitterrand was on the stage, no one else could really aspire to be the Boss, so it’s not too suprirrisng that it’s after his retirement from public affairs that Mélenchon started off his own party. In a way, Mitterrand’s dealing with nationalist groups is a good prediction of the fact that the PS moved to the right in the mid-1990s, sustained by a generation of socially more conservative leftists, whose Christian proclivities were not as much of the JOC type. Mélenchon is an old fashioned JOC-type: he stated in an interview that he reads the Bible, and he frequently gives interviews to Catholic papers, but h e might be the only one to have moved to the left of the left in the 1990s. Starting with Lionel Jospin and Ségolène Royal, there is a looming generation of politicians in the 1990s who although they’ll maintain (as Royal did) that faith is a private matter, are certainly not super warm to LGBTQ rights because of their personal beliefs. As a Prime Minister under Chirac, Jospin, ironically, is responsible for the passing of the civil contract in France, one of the major advances of LGBTQ rights in France in the 1990s–but what at the time was presented as a concession to the more conservative sensibilities of some MPs of the PS (to not go for marriage equality) increasingly looked like a personal choice when in the early 2000s, under pressure from their Green allies, the PS established marriage equality in its platform, to the protests of Jospin.

Perhaps it’s easier to understand Mélenchon’s position here too if one remembers his mother was excommunicated from the Church when his parents divorced–as he has said multiple times, he distrusts the Church as an institution, but he doesn’t dislike faith, and seems more religious than Hollande was (Hollande publicly said he did not believe God exists).

Growing up politically under Mitterrand’s influence has made Mélenchon a very egotistical politician–when his HQ was raided by police on suspicion of financial malversation in the 2017 campaign, he slapped a police officer and proceeded to bar access to the door, spouting “L’Etat chest moi.” (people who know French history will recognize the Louis XIV authoritarian quote: the state is me-I am the State).

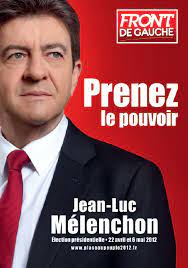

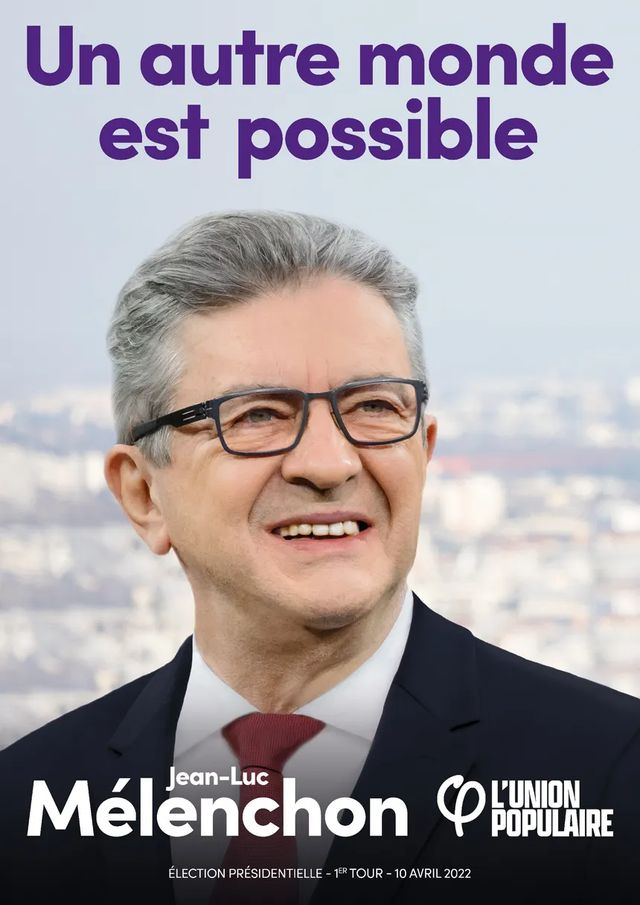

The flyer here is remarkably similar to the one Nathalie Arthaud’s team produced. A close-up of the candidate, looking above the shoulder of the audience, towards the future, although, weirdly, here, the candidate looks to the right, but that might be more a technical issue of not reversing the picture rather than a deliberate choice. Visually, I find this poster hilarious: the forced smile that is supposed to incite optimism and the idea of the future (which should pair well with the slogan “another world is possible”) instead makes you wonder what he ate to make that sour face. Fish that went bad? Too many prunes?

By contrast, his 2017 poster was much better:

Strength, determination, calm: those are all great qualities to project, not “OMG find me a bathroom now”.

Interestingly, or remarkably, as you want, the red that is normally associated with his party has completely disappeared, perhaps in an effort to appeal with the people who are fleeing from the Socialist Party (polling at a maximum of 3%) and the Greens (polling at 4.5%–under 5%, parties don’t get reimbursed for their campaign. It’s out of pocket, which almost sunk the Republicans after the disastrous 2019 European campaign, after they limped above the 8% mark, while already under a heavy debt burden from the Sarkozy years–all the French major parties have huge debts, including the Le Pen party, which owes millions to a Russian bank, hence the weird line MLP is playing with Putin).

I mean it’s not just that the closer picture and angle is not great with the red tie combination, it’s also the background that’s not contributing, and the smile. The. Smile.

My flyer is slightly different than the campaign poster: it has some verbiage under the picture and by virtue of contrast, the picture looks even more out of whack in terms of exposure than it does here. There are also a couple of campaign promises points below, none of which are particularly defined, but they underscore the priorities of the party, with three particular items in bold blue letters: real gender equality, send France to an alternative ecological path, and become a non-alined anti-globalization nation. I find interesting that the proposal of changing the constitution to the 6th Republic is not in bold here. It’s a left-wing proposal that’s been fairly popular in the left wing of the Socialist Party, mainly because the 5th Republic’s constitution is the brainchild of De Gaulle, but it’s not a proposal that has a significant traction outside of the left.

Also, render unto Caesar and all that: the guy has some guts. On the back of the flyer that came in the mail for us there is another picture. At first I thought that was a better picture than the front one, but no: it’s the cover of his memoirs/political pamphlet, published with Seuil publishing. Under the guise of a flyer the state distributes for free for the parties, Mélenchon sells his book. I’m not sure it’s moral, but it’s apparently legal, dear reader.

The picture sort of takes the cake though: when I got it out of the enveloppe we received for the vote, I laughed out loud. It’s already increasingly hard to take seriously a guy who uses holograms and odor projectors for his meetings, I…

I don’t know what to tell you. Sometimes marketing and consultants are not great (see the McKinsey consulting scandal Macron is currently dealing with).

Also, side note, this picture looks eerily like the one he already used for his 2012 poster, but aged and cut off. It worked way better in 2012–well it worked better if you were going for the revolution and class clash: