Teaching Philosophy Statement

It is 10:30 am, and there is a shuffle of feet and laughs in my French class. I have divided students into three groups, each with its own selection of lyrics from a song. They have been tasked with reading the excerpts and trying to guess the meaning of what they do not know using the context that they have gathered from the words that they do know. As I go through the definitions they have written on the board, I see students realize that they can understand meaning on their own, and smile at the idea that they know far more than they are aware of.

The above example reflects not only my central belief in teaching, but also how I teach. I do not want students to simply skim a text and learn a language; I want them to interact with French. I want them to develop critical skills that will allow them to make the leap of faith that I have asked of them, again and again, on their own, whether the classroom or in their lives. Whether I teach literature, language, or history courses, the reason why I am passionate about what I do is because teaching is, in my mind, a collaborative process through which the students form or deepen an attachment to the language and cultures of the Francophone world, while improving reading and writing skills as well as critical thinking. This endeavor is based as much on their own personal skills and interests, which I foster and cultivate, as the taste for language-learning they will develop, which I lead them toward.

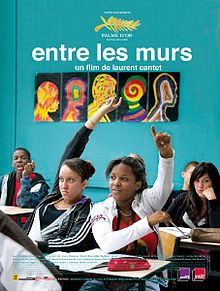

In a recent class, for example, we discussed a film, Entre les murs, and a bande-dessinée, Retour au collège. Both introduce students to French schools: one in a low-income neighborhood, and the other in a high-income one. For each source, I broke down bigger questions of class and race, asking students about issues that they could relate to, such as the language abilities of their fictional counterparts, or the qualities that allowed them to identify with one character or another. Initially, discussions were led in small groups, whose conversations I facilitated, after which the class reconvened together. Students pointed out their perceived parallels and differences between French classrooms and those at Brown: the continuous struggle with increasing and maintaining diversity, and clothing as a cultural marker—and the class had a good laugh about the latter, as it led to remarks about the thrift-store clothing culture at Brown!

In a recent class, for example, we discussed a film, Entre les murs, and a bande-dessinée, Retour au collège. Both introduce students to French schools: one in a low-income neighborhood, and the other in a high-income one. For each source, I broke down bigger questions of class and race, asking students about issues that they could relate to, such as the language abilities of their fictional counterparts, or the qualities that allowed them to identify with one character or another. Initially, discussions were led in small groups, whose conversations I facilitated, after which the class reconvened together. Students pointed out their perceived parallels and differences between French classrooms and those at Brown: the continuous struggle with increasing and maintaining diversity, and clothing as a cultural marker—and the class had a good laugh about the latter, as it led to remarks about the thrift-store clothing culture at Brown!

However, building on what students know also often means alleviating anxieties about what they do not know, and reshaping students’ stereotypes. When discussing the concept of laïcité in France, in French VI, I split the class in two groups to organize a debate on the law against religious signs in French schools. In the first, I intentionally placed students who had expressed the most negative initial reaction to the concept of laïcité in class, and asked them to defend the law. After the debate, during the debrief session, students emphasized that defending the law allowed them to understand its cultural and historical context, and then questioned my own understanding of the law, stating that it was based on a dystopian premise of neutrality, as differences such as skin color are not something that one can leave at the door of a classroom. In instances such as this, I know my class has been effective, because both the students and I have to think differently and critically: defending a point of view they are unfamiliar with leads students to internalize cultural difference and understand it—just as I assimilate a different outlook on French culture every time we have debates like this in class.

The effectiveness of this collaborative method, amongst students and between students and I, is also revealed through the development of students’ written productions, which are varied and make extensive use of students’ imagination and creativity. At Brown, my first French V class was tasked with developing a roman-photo, starting with a storyboard. In every group, I gave extensive feedback, both to the group and to individual students. I also participated in one of the groups’ work as the Patient Zero of a zombie outbreak! The personal involvement students felt with this assignment was highly effective in providing context for vocabulary and grammar, positively reinforcing their relationship with French: the following written assignment was significantly better for most of that class, not only in form, but also in content and critical skills.

At Montclair State, I assigned to students a creative project in which they had to advertise their university, after we had developed together in a lecture an understanding of how advertisement works and the specific vocabulary it uses. To make sure there was fairness in time demands and vocabulary and grammar use, the students had to explicitly write out which advertising targets they were trying to influence, how their ads would be displayed, along with schedule and format, and analyze how their and their peers’ projects worked, after the in class presentation. One group produced a commercial, using the one-shot method (students shoot the movie/clip in the order it runs, and there are minimal editing skills needed) that used the nearby biology green building and its gorgeous view of Manhattan as a selling point for the building and the School of Arts and Sciences.

At the College of Staten Island, written production was more limited, since the students were in their first semester of French, but one of my classes took to inventing stories about the book’s short movies demonstrating vocabulary. After each segment, we would jokingly comment on what happened, as if the characters of the academic textbook were the protagonists of a popular telenovela. While the students never once considered this a serious academic exercise, it indeed was, and allowed them to develop vocabulary, self-confidence, and made the class more welcoming, especially since the vast majority of my students were Latinx and/or black students. The mostly white cast of the educative sequences did not speak to their experiences, but turning this into a TV show they produced unknowingly related to the world outside the classroom they knew best. In cases like this, I consider that grades or rules can be an impediment to knowledge, and I am always happy to use low-tension settings like this to help students.

All of my experiences reinforce the central point that I hope to have made in this teaching statement: teaching is a constant conversation—with students, with colleagues, with the world outside our classroom. It is incredibly rewarding to see students develop an organic relationship with French—and in the past, this relationship to the language has blossomed into a beautiful love story, complete with a semester abroad for many students in my classes, or requests for educational readings/films they could watch–I once had a student ask me a list of French philosophers to be read in English (she was in French 101), and whom she spent the summer reading! For all of the students I have taught, my goal is to help them cultivate their own understanding of the interconnected communities they live in, something students can achieve by practicing one of the original global languages in an engaging, dynamic and open classroom.

Leave a comment